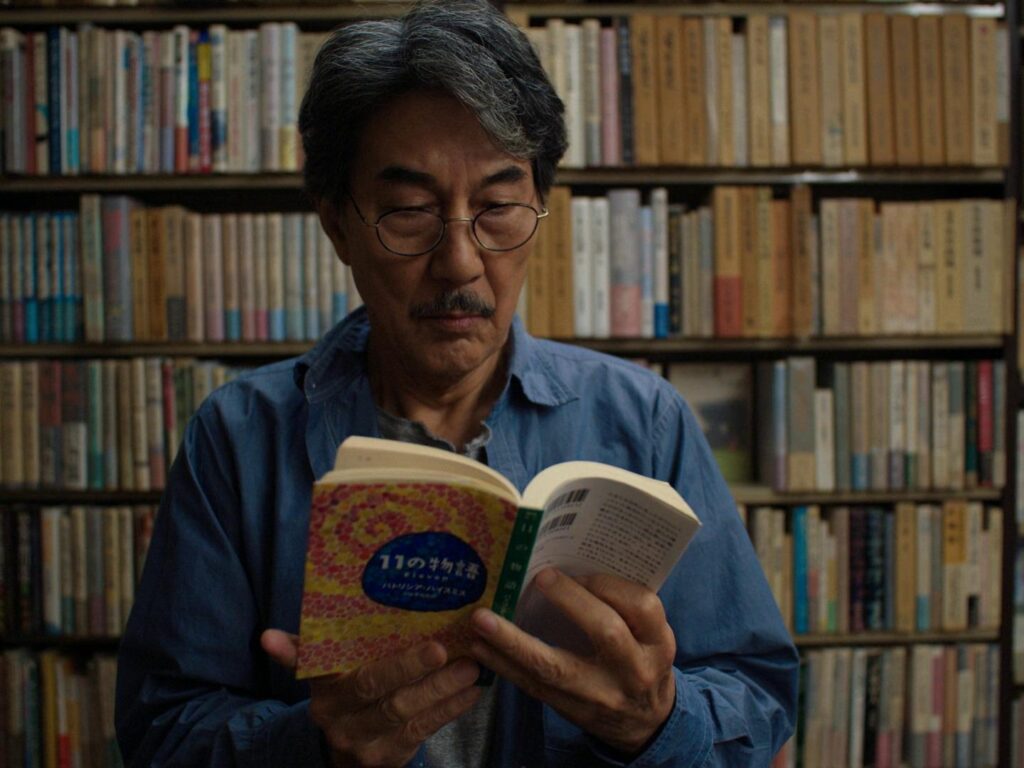

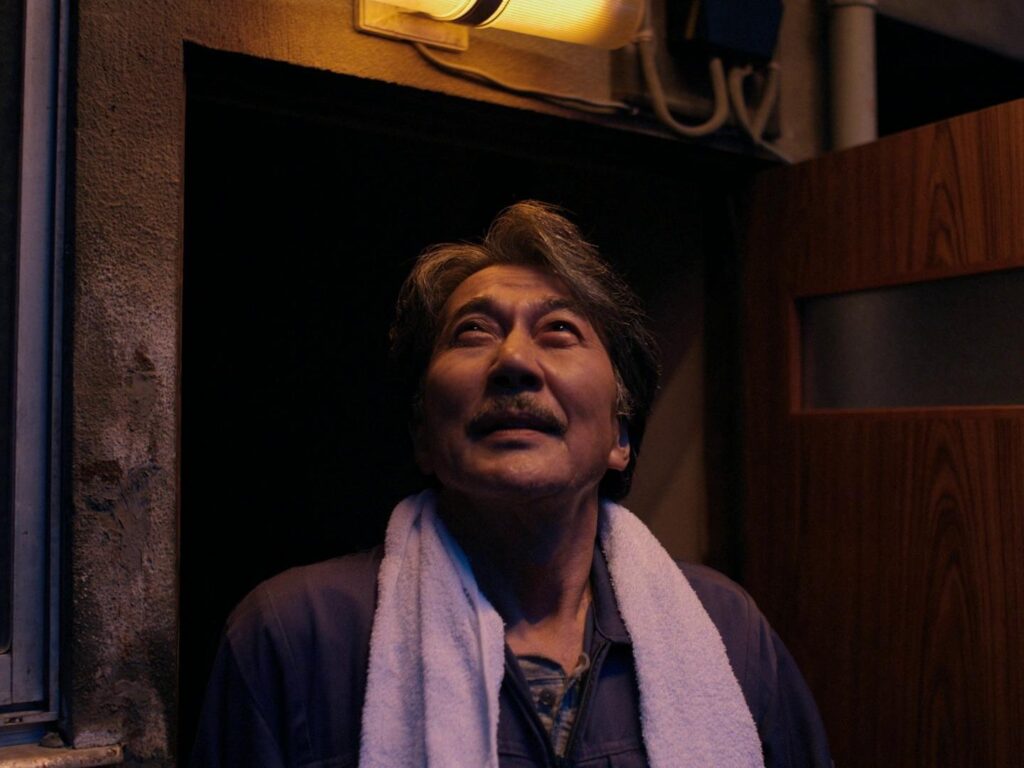

Few films capture the texture of everyday life in Tokyo with the precision and humility of Perfect Days (2023). Directed by Wim Wenders and carried almost entirely by the masterful performance of Kōji Yakusho, awarded Best Actor at the Cannes Film Festival, the film follows Hirayama, a middle-aged man working as a toilet cleaner in Tokyo’s Shibuya ward.

Wim Wenders and the quiet weight of existence

Hirayama’s life unfolds through repetition: waking early, tending to his plants, driving to work, cleaning public restrooms with meticulous care, eating simple meals, bathing at night, and reading before sleep. Day after day, the rhythm barely changes. At first glance, he appears serene, even content.

Yet beneath this calm surface lies a quiet existential tension that places Perfect Days firmly within the lineage of Wenders’ earlier cinema. Like the wandering protagonists of Alice in the Cities (1974) or Wrong Move (1975), Hirayama inhabits a world marked by disconnection and introspection. The difference is that movement itself, once the engine of inner exploration, has been stripped down to near immobility. Where Wenders’ 1970s characters roamed landscapes in search of meaning, Hirayama circles within a dense, claustrophobic cityscape, confined to daily commutes and familiar streets.

In this reduced geography, meaning is sought not through travel but through repetition. Hirayama’s repeated gestures, cleaning toilets that will inevitably be dirtied again, echo the figure of Sisyphus. The absurdity of the task is not denied, it is embraced. In this sense, the film quietly dialogues with Albert Camus’ philosophy: rebellion not as defiance, but as the lucid acceptance of life’s absurdity. Hirayama’s voluntary social descent, subtly revealed through a visit from his affluent sister, confirms that his life is the result of choice rather than resignation.

Objects play a crucial role in anchoring Hirayama to the material world. His cassette tapes, paperback books, analog camera, and carefully nurtured plants stand in resistance to a society dominated by dematerialization and speed. Light and shadow, in particular, become recurring motifs. Hirayama’s fascination with sunlight filtering through trees (“komorebi” in Japanese, as specified at the end of the film), photographed obsessively, suggests a search for proof that things exist, that moments matter. Even his dreams, rendered in abstract black-and-white forms, refuse narrative clarity, pointing not backward toward explanation but inward, toward an unresolved interior landscape.

The film’s structure mirrors this philosophy. Its initial slowness lulls the viewer into a meditative state before subtly accelerating, drawing us beneath the apparent tranquility and into the character’s emotional undercurrent. Perfect Days does not offer resolution. Instead, it invites acceptance of ambiguity, solitude, and the fragile beauty of the present moment.

When fiction overlaps with reality

When Perfect Days was released in Japanese theaters in late 2023, it felt like a film I needed to see, not only for its subject matter, but also because I was curious to see Kōji Yakusho under the direction of Wim Wenders, a filmmaker whose magnificent films like Paris, Texas (1984) and Wings of Desire (1987) had deeply impressed me. However, I did not expect how deeply personal the experience would become.

Hirayama does not live in an anonymous Tokyo, he lives in Sumida, my own neighborhood. His apartment, tucked behind Koto Tenso Shrine, exists in the shadow of Tokyo Skytree, its glowing silhouette hovering over the skyline. The streets he cycles through, the sentō he visits after work, the bridges he crosses (Sakurabashi in particular) were all places woven into my own daily life. Watching the film, I was struck by the uncanny sensation of seeing my surroundings reframed through cinema.

The parallel went beyond geography. Hirayama is a solitary figure, navigating Tokyo quietly, attentively, without spectacle. His routine, his relationship to silence, and his way of inhabiting the city resonated deeply with my own experience of living in Japan, especially knowing that the film was shot around the time I arrived in the country. Like him, I was learning how to exist in a place where meaning is often found not in expression, but in restraint.

The locations themselves contribute powerfully to this resonance. Asakusa and Sumida embody a Tokyo that feels lived-in rather than consumed. Denkiyu, the neighborhood sentō, remains a community space where generations intersect without ceremony. Chikyudo Books, with its ¥100 paperbacks and early closing hours, feels like a quiet refuge from the city’s noise. Sakurabashi, whether crossed at sunset or lingered under at night, offers a breathtaking view of the Sumida River, which separates the ward of the same name from Taito-ku. Even places like Asakusa Yakisoba Fukuchan or the fictional bar Beni no Akari Novu carry this same intimacy. They are not destinations in the touristic sense, but everyday anchors, places where life unfolds modestly, where familiarity replaces novelty.

In Perfect Days, these locations are collaborators, shaping the emotional landscape. The film’s impact is even stronger now because I met my wife in Asakusa a few months after its release, and that very place appears in the film. Watching it again together, it was both funny and fascinating to recognize all those familiar places from our daily lives.

What moved me most was not recognition, but reflection. Seeing a fictional life unfold so close to my own physical reality forced me to consider the quiet parallels between cinema and lived experience. Like Hirayama, I was slowly learning that meaning does not always announce itself. Sometimes, it reveals itself only in repetition, in attention, and in the acceptance of the present moment, just as it is. In that sense, Perfect Days did not merely depict Tokyo. It mirrored a way of living within it.

The film did not just leave me with the impression of having seen a beautiful film, it subtly altered the way I perceived my own (perfect) days. Long after the screening, Hirayama’s gestures (his peaceful routines, his attention to light, his acceptance of solitude) continued to resonate in my daily life in Sumida. Walking the same streets, crossing the same bridges, I realized that the film had revealed something I was experiencing, a kind of presence rooted in repetition, modesty, and attentiveness.

Wenders’ film suggests that meaning does not necessarily arise from movement, ambition, or transformation, but from a sustained engagement with the present. In my own experience in Japan, far removed from the expectations I once associated with living abroad, I found a similar lesson. Like Hirayama, I have learned to inhabit time differently, to accept stillness, to find comfort in routine, and to recognize that solitude can be fertile rather than empty. As he repeats to his niece Niko on the Sakurabashi Bridge: “Kondo wa kondo, ima wa ima” (“Next time is next time, now is now”).

Image credits: Film stills from Perfect Days (2023), directed by Wim Wenders. Stills sourced from FilmGrab.