On the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II, Louise George Kittaka visits two cities whose names are inextricably linked to the universal longing for peace, while reflecting on what it has meant to her own family.

“the day nuclear weapons disappear from the earth.” (Courtesy of Hiroshima Tourism Association)

Standing before the Hiroshima Peace Museum, I feel a quiet unease about what awaits inside. As I step through the entrance, I brace myself to confront the human stories behind one of the world’s darkest moments—the atomic bombing of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945.

My mind drifts back to my first visit as a 20-year-old university graduate, more than thirty years ago. I had recently arrived in the city of Fukuyama in Hiroshima Prefecture on training for my first job. A British friend and I took a day trip from Fukuyama down to Hiroshima City for sightseeing and, of course, the world-famous Peace Museum was on our list.

Facing the tragedy of the past

Inside, we were confronted by a diorama of three lifelike wax figures—a mother, her child and a schoolgirl—with burned flesh and anguished faces, fleeing the city after the bombing. The sight seared itself into my memory and haunted my dreams for months.

Not long after, I met my future husband, who was born and raised near Fukuyama, and 15 months later I was beginning newlywed life there. We moved around for our jobs, adding three children along the way and eventually settling in Tokyo. We visited Hiroshima Prefecture frequently to see relatives and friends over the years, but I couldn’t bring myself to revisit the museum, fearing the exhibits were too harrowing.

Finally, some three decades later, I have returned. The wax figures, a fixture since 1973, have gone. The museum closed for renovations in 2014, and when it reopened four years later, the figures were no longer on display. In that time, museums around the world have evolved, using personal stories to drive their exhibits. Today, these narratives—supported by documents, artifacts, testimonies and digital techniques—make history more immersive and reflective.

The first time I left the Hiroshima Peace Museum I was a young woman, unable to see beyond my own feelings of horror. Today, I walk out as the mother of young adults, my heart heavy with the loss of lives and unfulfilled dreams, but also with quiet determination that my children—and the generations to come—must never experience the devastation of war. Remembrance, I now see, is not only about grief but about carrying forward the resolve to protect peace.

Passing the baton to a new generation

Hiroshima-based Peace Culture Village (PCV) runs programs that encourage people in Japan and abroad to consider how we can all contribute to a more peaceful world. Its flagship initiative, Peace Dialogue, trains young “Peace Buddies” to guide student groups through the Peace Memorial Park. For decades, hibakusha (A-bomb survivors) were the main storytellers, but as they age, the project is cultivating a new generation to carry their voices forward.

“Among the Peace Buddy members—high school and university students as well as young professionals—some are from Hiroshima and wish to share what they’ve learned about their hometown. Others come from elsewhere and want to learn deeply about Hiroshima while they live there, using it as a starting point for thinking about peace,” says Mayu Seto, Peace Education Director for PCV.

Another initiative, newly opened in 2025, is the Peace Culture Museum, which embodies the wisdom and vision of Toshiko Tanaka, an A-bomb survivor and pioneering enamel wall artist. Having lived through the atomic bombing at the age of six, she has devoted her life to advocating for the abolition of nuclear weapons. This museum uses the power of art to connect the reality of the past with a vision of a peaceful future.

On a wing and a prayer

The Children’s Peace Monument in Hiroshima’s Peace Memorial Park is one of the city’s most recognized symbols, inspired by the story of a young girl called Sadako Sasaki (1943–1955). A survivor of the bombing, Sadako later developed leukemia and began folding one thousand paper cranes (orizuru) in the hope of recovery. She died at age twelve, but her story and the cranes she folded continue to embody the universal wish for a world free of nuclear weapons.

Some 10 million paper cranes wing their way to Hiroshima annually, folded by people all over the world. With a view to promoting ethical consumption and sustainability, local firm Earth Hiroshima recycles these paper cranes into paper called Re:Orizuru, which is then used to create a wide range of products. The company also supports Hiroshima-based businesses in developing and promoting products that showcase the charm of the city.

During my visit, I take part in one of their craft workshops—a new experience aimed at inbound visitors—to make a lovely three-dimensional flower out of Re:Orizuru paper. With my creation tucked carefully inside a box (naturally also made from recycled paper), I feel as though I am taking a tiny part of Sadako’s enduring legacy home with me.

Living in the lingering shadow of war

In the years following the war, Hiroshima’s residents were urged to focus on reconstruction as the city rose from the ashes of devastation. While there was sympathy for the hibakusha, they were also a painful reminder of a past many wished to move beyond during Japan’s drive to rebuild.

Living at the other end of the prefecture, my husband’s family was not directly affected by the bombing, though some neighbors who had gone to visit Hiroshima City never returned. My mother-in-law’s parents, both teachers, relinquished their positions to work the family farm so they wouldn’t have to sell their land under postwar reform policies.

In her early teens at the end of the war, my mother-in-law was a gifted student, but her opportunities were limited by gender and circumstance, and her parents could only afford to send her brother to university. She followed a traditional path, marrying through an introduction and raising three sons, while taking on work at home for a relative’s business. She nursed her husband through illness and later cared for her own mother-in-law, always putting everyone else’s needs ahead of her own.

When she passed away in 2017, it was revealed that few in her family knew her birthday, including her own children. Her sister finally told us why: my mother-in-law was born on August 6. Although still a middle school student in 1945, she could no longer bring herself to celebrate a date that had caused so much suffering in her prefecture.

A voyage for peace; waves of understanding

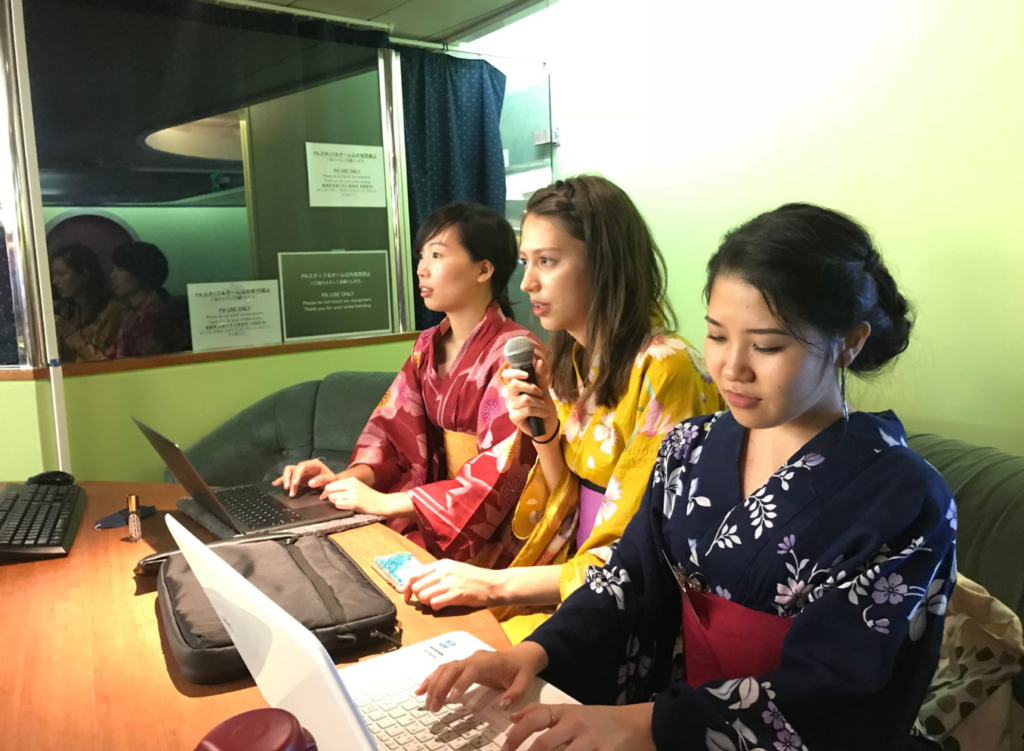

Six months after she passed away, her 20-year-old granddaughter—my daughter—boarded the Peace Boat as a volunteer translator for a voyage around Asia and the Pacific. Peace Boat, a Japan-based NGO, promotes peace through educational voyages. It is also a partner of ICAN (the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons), a global coalition that calls on governments to eliminate nuclear weapons and was awarded the 2017 Nobel Peace Prize for its efforts.

Several elderly hibakusha from Hiroshima and Nagasaki were on board, sharing testimonies and speeches at stops along the way. My daughter, then a second-year medical student in New Zealand, was among those who interpreted for them. She found the experience life-changing, and it strengthened her wish to advocate for marginalized patients in the New Zealand health system. After qualifying as a doctor, she chose to work at a hospital in Auckland’s lowest-income health board area, where many patients are immigrants facing language barriers or people with lifestyle diseases often linked to poverty.

If my mother-in-law had been born in a later era, who knows where her quick mind and quiet determination might have taken her. She firmly believed in the value of hard work and doing one’s part, and she would have been very proud of her granddaughter’s path. It also gives me pause to think that eighty years ago, New Zealand and Japan were at war, and yet today my own children are making their way in the world with both heritages intertwined.

Nagasaki’s message to the world

I head to Nagasaki, which was the target for the second atomic bomb on August 9, 1945. I meet another group with strong ties to ICAN—Peace Education Lab Nagasaki (PLAB)—and take part in a tour around Nagasaki Peace Park with one of their young guides. The tour isn’t simply a one-way lecture; it feels like a shared journey. As we walk, the guide encourages open conversations, and we pause often to ask questions and exchange thoughts that could only arise in this place, shaped by its history and atmosphere.

At the Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum, I see a clock frozen at 11:02 a.m.—the moment the bomb exploded. Surrounding it, exhibits of personal belongings, images and stories convey the city’s suffering and determination to rebuild. “If Hiroshima was first, Nagasaki should be the last” became a solemn vow that such a tragedy must never be repeated.

Mitsuhiro Hayashida, Representative Director of PLAB, is deeply involved in ongoing efforts to honor the legacy of the hibakusha while fostering understanding among younger generations. He has maintained ties with ICAN for more than a decade, coordinating Nagasaki-based events for the organization. He also formerly served as Communications Representative for the Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations (Nihon Hidankyo), winner of the 2024 Nobel Peace Prize, and was among representatives who attended the award ceremony in Oslo, Norway.

Hayashida points out that conflicts often arise when differing senses of justice collide, each believing it stands “for peace.” Traditional peace education in Japan has often focused on the fear of war and nuclear weapons, with fewer opportunities to consider how such tragedies can be prevented. “So, when teaching about the history of war, we emphasize studying events from multiple international perspectives, not only Japan’s.”

“Many young participants finish our programs inspired to consider what they themselves can do. We hope to continue nurturing this sense of agency—helping them realize that the future is not made by others, but also by themselves,” says Hayashida. To this end, PLAB also works closely with PCV in Hiroshima, visiting each other’s cities to experience programs firsthand and share insights.

Illuminating the past to guide the future

Reflecting on what I have seen and learned in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, I am reminded of another cultural touchstone for Japan’s wartime experience—the 1988 Ghibli anime Grave of the Fireflies, directed by Isao Takahata. It tells the story of two siblings, 14-year-old Seita and four-year-old Setsuko, war orphans in Kobe who are starved of food and familial affection during the final months of war. The achingly sad story has been widely acclaimed both in Japan and around the world.

Based on Akiyuki Nosaka’s 1967 novella of the same name, which won the prestigious Naoki Prize, the first stand-alone English edition has just been released by Penguin Classics. The new translation is by Ginny Tapley Takemori, who describes the process as both painful and yet absorbing, akin to solving a puzzle.

“Ultimately, I was inspired to take on the work because it is an extremely important story, and I want everyone to read it,” she says. “Especially now, as conflicts spread dangerously around the world, it feels more crucial than ever to remind people of the realities of war—and why we must do everything in our power to avoid or resolve them.”

Her words echo the messages I have heard in Hiroshima and Nagasaki: remembrance alone is not enough. The stories of those who suffered—and those who continue to share their light—remind us that peace is never guaranteed. It must be protected and nurtured by every generation.