Often translated as “pictures of the floating world,” ukiyo-e is inseparable from the city that gave it life. Born in Edo (present-day Tokyo) during a time of rapid urban growth, social transformation, and cultural effervescence, ukiyo-e emerged as a visual language of everyday pleasures, intimate, ephemeral, and profoundly modern. Far from being confined to studios and bookshops, it was shaped by geography, waterways, leisure districts, and the rhythms of daily life.

Among the places that quietly nurtured this art form, Sumida ward (and particularly the Mukojima neighborhood) occupies a singular position. Situated just beyond the dense urban core, this riverside area preserved landscapes, customs, and atmospheres that connected Edo’s present to its past. For artists seeking both inspiration and distance, Mukojima offered an ideal vantage point, close enough to observe the city’s vitality, yet far enough to evoke nostalgia, nature, and memory.

Landscapes, leisure, and the everyday world

The origins of ukiyo-e cannot be separated from Edo’s geography. From the early 17th century onward, the city developed alongside an intricate network of rivers, canals, and artificial waterways designed both to control flooding and to facilitate transport. The Sumida River, in particular, was a lifeline economically, socially, and culturally. Boats carried goods, people, and ideas, shaping a city where movement by water was often more natural than movement on foot.

Within this watery landscape, Mukojima stood apart. While nearby Honjo suffered devastating destruction during the Great Fire of Meireki in the mid-17th century, Mukojima remained comparatively rural and loosely developed. This difference would prove decisive. As Edo expanded and densified, Mukojima preserved an atmosphere shaped by open spaces, embankments, riverside paths, and leisure establishments. By the late Edo period, it evoked a vision of an older Edo, one shaped as much by nature as by human intervention. It was precisely this quality that drew ukiyo-e artists.

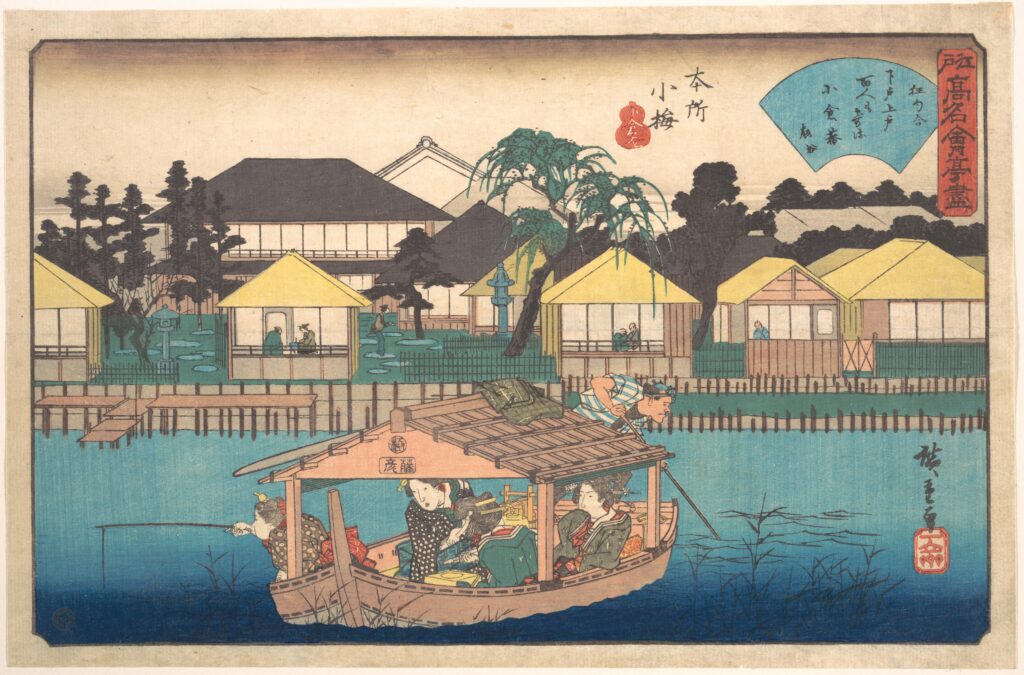

For painters such as Hiroshige Utagawa, Mukojima offered a setting where nostalgia, landscape, and everyday life converged. Restaurants, teahouses, bathhouses, and pleasure spots lined the Kitajukken River, welcoming visitors who arrived by boat to eat, bathe, and relax. Ukiyo-e prints captured these scenes with remarkable intimacy: women changing into yukata after bathing, diners overlooking the water, seasonal gatherings beneath blossoming trees. These were fragments of lived experience, recognizable, accessible, and deeply familiar.

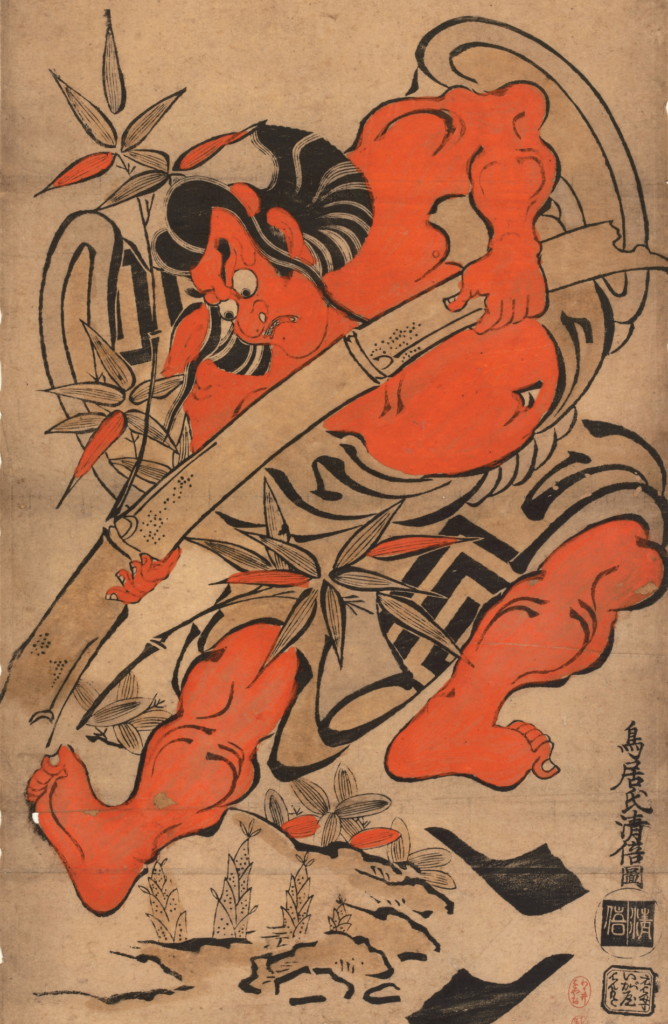

Ukiyo-e itself emerged from such familiarity. Initially, prints served as illustrations accompanying text, produced in black ink using woodblocks. One of the earliest innovators was Kiyonobu Torii, founder of the Torii school, whose work was closely tied to kabuki theater. Early prints were monochrome, but color soon entered through experimentation. Red pigment, known as tan, was applied by hand to black-ink prints, resulting in uneven, sometimes rough coloring. Though technically limited, this was revolutionary. Color transformed prints into desirable objects, bridging the worlds of illustration and independent art.

The Torii school became synonymous with kabuki imagery (actor portraits, stage scenes, and theater signboards) developing a bold visual style with thick lines and powerful poses. Kabuki and the Yoshiwara pleasure district formed what authorities called the “two great villains” of Edo: morally suspect, yet irresistibly popular. Ukiyo-e artists embraced these subjects, depicting actors and courtesans who became early visual icons. At first, faces were standardized, emphasizing role rather than individuality.

This changed with Shunshō Katsukawa, who introduced realistic actor portraits with distinct facial expressions. His innovation marked a turning point, expanding ukiyo-e’s expressive potential and popular appeal. Among his pupils was a young artist from Sumida: Hokusai Katsushika, whose lifelong engagement with the area would later reshape ukiyo-e itself.

Another decisive transformation occurred with Harunobu Suzuki, whose work was closely tied to Mukojima’s cultural circles. Harunobu played a central role in the development of nishiki-e, or full-color prints, made possible through precise registration techniques that aligned multiple color blocks. His involvement in producing egoyomi, decorative illustrated calendars exchanged among poets and connoisseurs, pushed technical innovation forward. More importantly, Harunobu shifted ukiyo-e’s focus toward ordinary people, such as teahouse waitresses, young couples, everyday scenes, rendered with poetic delicacy.

As Edo’s population grew, fueled in part by reconstruction after fires, so did the audience for such images. Prints were affordable, sold in illustrated bookshops where samurai and townspeople browsed side by side. Artists expanded their subjects to include sumo wrestlers, famous beauties, local celebrities, and eventually landscapes. Series depicting the Sumida River unfolded like visual journeys, showing its banks across seasons and moods. These images were often paired with kyōka, playful poems that added wit and intimacy to the viewing experience.

By the late Edo period, landscape ukiyo-e had become an independent genre. Works such as Edo Meisho Zue (“Guide to famous Edo sites”) and later Hiroshige’s celebrated views transformed familiar places into enduring images. Shrines, torii gates, teahouses, and river landmarks around Mukojima appeared again and again, anchoring memory in place. Though many original works were lost to disasters such as the Great Kantō Earthquake of 1923, their survival through modern reproductions, now displayed in institutions like the Sumida Hokusai Museum, testifies to their lasting significance.

From Edo to Europe: Ukiyo-e and the birth of Japonisme

As Japan reopened to the world in the mid-19th century after more than two centuries of isolation, its art arrived in Europe with surprising force. Among the many cultural objects that flowed into Western markets (textiles, ceramics, lacquerware), ukiyo-e woodblock prints quickly captured the imagination of European artists. Their flat planes of color, bold compositions, innovative use of line, and novel sense of space stood in striking contrast to Western academic painting, which emphasized perspective, shading, and modeled form. This visual language, simultaneously exotic and refreshingly direct, helped spark a phenomenon known as “Japonisme”, a fascination with Japanese art that transformed European aesthetics, especially in France.

The term Japonisme came into widespread use in the 1870s to describe the craze for Japanese art and design among collectors, designers, and painters in Paris and beyond. Ukiyo-e prints were at the forefront of this movement; they were collectible, affordable, and visually immediate. Claude Monet, for example, amassed a large collection of Japanese prints by Hokusai and Hiroshige at his home in Giverny, arranging them around his living space and studying their compositional strategies. Monet’s interest in asymmetrical balance, flattened space, and vibrant color (features he incorporated into his series paintings of water lilies, haystacks, and poplars) owes much to his engagement with ukiyo-e aesthetics.

Vincent van Gogh was perhaps the most fervent ukiyo-e enthusiast among the Post-Impressionists. He collected dozens of prints, especially those by Hiroshige, and even reproduced several by hand in oil, adapting their flat color areas and compositional framing into his own expressive style. Van Gogh wrote that “all my work is based to some extent on Japanese art”, reflecting how deeply he internalized its visual vocabulary.

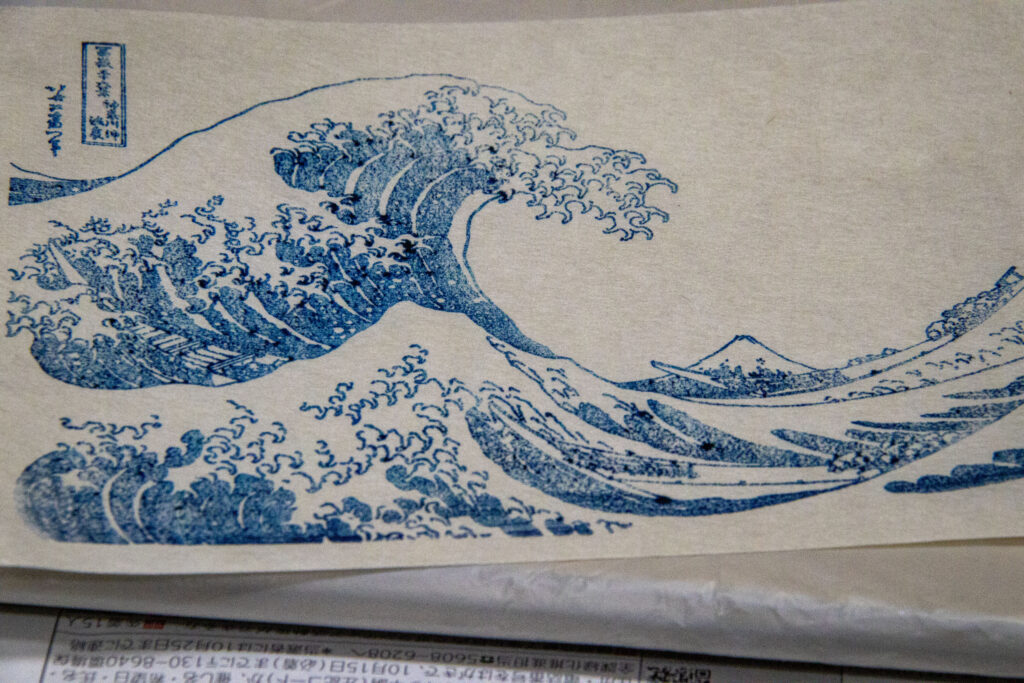

The influence extended beyond painting into other arts as well. Claude Debussy, the French composer, was moved by Hokusai’s The Great Wave off Kanagawa during his work on the orchestral piece La Mer (The Sea). Debussy reportedly kept a copy of the print in his studio and requested that it be used on the cover of the original 1905 edition of the score, symbolizing the work’s connection with Japanese aesthetics and the elemental power of the sea captured in both image and sound.

Other artists and designers also absorbed ukiyo-e’s influence: Edgar Degas explored Japanese compositional ideas in his prints and paintings; Henri Rivière created his own series Les 36 Vues de la Tour Eiffel in homage to Hokusai’s series; and the flattened perspectives and decorative motifs of ukiyo-e fed into the emerging Art Nouveau movement across Europe.

The creative process of mokuhanga

The traditional craft of mokuhanga, the Japanese woodblock print, reveals a method as layered and rhythmic as the prints it produces. Rooted in craftsmanship that flourished alongside ukiyo-e during the Edo period, mokuhanga blends meticulous manual skill with deep material awareness, bringing both image and atmosphere alive on paper. The workshop at Kataoka Byobu Shop in Mukojima offered a window into this process, grounding participants in both historical practice and hands-on technique.

At the heart of mokuhanga is washi, traditional Japanese handmade paper. The strength and softness of washi make it ideal for absorbing water-based color, yet it is subtly textured and delicate to the touch. During printing, the paper is dampened before use, a crucial step that ensures the ink settles smoothly and evenly into the fibers, avoiding blotches or inconsistencies. This practice reflects a core mokuhanga principle: careful preparation yields clarity in the final impression.

The pigments used are water-based, mixed with a small amount of starch glue and sometimes animal glue, which helps the color adhere properly and prevents the paper from distorting during pressing. The instructor emphasized that the paint-to-glue ratio, commonly around three parts pigment to one part glue, affects both hue strength and the fluidity of the application, creating deeper, cleaner tones when balanced correctly.

A mokuhanga workshop highlights how ink and paper must work together. Unlike many Western print methods that rely on a press, mokuhanga uses a baren, a flat, palm-sized disc traditionally made by wrapping bamboo fibers, to manually transfer the ink from the woodblock to the paper. By rubbing the baren across the back of the paper in steady, controlled motions, the printer encourages the inked design to imprint clearly.

One of the most essential aspects of mokuhanga printing is registration: the precise alignment of paper across multiple woodblocks to ensure each color layer lands exactly where it should. In traditional practice, woodblocks are carved with notches known as kento to guide positioning. This makes it possible to register multiple blocks so that even complex multicolor prints retain exact compositional harmony. These techniques were simplified in the workshop setting, but the principle remained.

Each color is printed in sequence, traditionally starting with the lightest tones, then building toward darker and richer hues. This incremental layering deepens color saturation and creates depth within the image. In traditional ukiyo-e, master artisans carved and printed with many more colors (six or more blocks were common), each block adding nuanced tones and subtle shading as part of a cumulative creative process.

In the Edo period, a mokuhanga print was a collaborative endeavor involving multiple specialists, an artist (eshi), a carver (horishi), and a printer (surishi), each contributing expert skill to realize the final artwork. The artist created the initial drawing, which was then transferred onto woodblocks. The carver, using chisels and knives, carefully removed unneeded wood from each block, leaving a relief that defined the design. Each color in the print required a separate carved block, all aligned through registration marks. Finally, the printer inked and impressed the design onto dampened washi using a baren.

In contrast, the Kataoka workshop employed pre-carved or laser-cut blocks to make the process accessible to participants of all levels. While these blocks lack some of the subtlety of hand-carved relief, they faithfully convey the tactile experience of mokuhanga and help learners understand the interplay between pigment, paper, and manual pressure. The core techniques (mixing pigments with glue, aligning paper, and rubbing with a baren) remain the same, offering a hands-on appreciation of how historical prints were made.

Participants were reminded that early impressions often appear light or uneven: this is inherent to the layering process. Over successive passes, color deepens and images gain clarity. This reflects mokuhanga’s essential philosophy, where art emerges from gradual accumulation and careful craft. The physical rhythm of rubbing the baren and the mindful attention required to align colors instill a sense of connection to materials, to technique, and to the history of an art form that has endured for centuries.

From floating worlds to printed worlds

From water-borne landscapes in Edo to ink-soaked impressions on washi, the journey of ukiyo-e is as rich and layered as the prints themselves. Its subjects, from kabuki actors to ordinary women, reflect a culture shaped by mobility, commerce, and the pleasures of urban life. In 19th-century Europe, ukiyo-e fueled Japonisme, reshaping visual culture and inspiring artists.

Finally, mokuhanga reveals the tangible artistry behind these prints, from the careful selection and preparation of washi paper, to the mixing of pigments and glue, to the rhythmic application of a baren. Whether carved by hand or produced in a workshop, the process itself embodies a blend of precision, patience, and aesthetic sensitivity that has endured for centuries. In exploring ukiyo-e and mokuhanga, we encounter a way of seeing: one that celebrates everyday beauty, skilled craft, and the flowing rhythms of life.